Christian Pro-Lifers usually reject out of hand quality-of-life arguments about abortion, insisting that only a sanctity-of-life understanding gives us a fully valid basis for making such judgments. The quality-of-life approach looks at the kind of life a problem-pregnancy would supposedly lead to, with its difficulties, and asks whether at some point such a life might be not worth living. The sanctity-of-life approach stresses the inherent worth of every human life because it is created in the image of God. Christians are right to insist on a sanctity-of-life ethic for many reasons. But I propose to accept a quality-of-life stance for the moment, for the sake of argument. Why? Because an attempt to do so will demonstrate that the quality-of-life argument for abortion fails, fails miserably, and can be shown to fail miserably.

Helen Keller

Pro-Choice arguments trying to spin abortion as a charitable act often focus on the various trials and hardships in life that a foetus unfortunate enough to be “unwanted” or handicapped is going to be spared. That seems reasonable until you apply it to some actual test cases. Let’s take a seriously handicapped individual who actually lived, Helen Keller. Did she think her life of such a quality as to be not worth living? It doesn’t seem so. Let’s try again. Does Stephen Hawking think his life of such a quality as to be not worth living? Would he, in other words, prefer non-existence to being bound to a wheelchair and having to talk through a computer? Clearly not; if he did prefer non-existence (assuming that is his concept of what death would be), he could surely arrange to have it.

Stephen Hawking

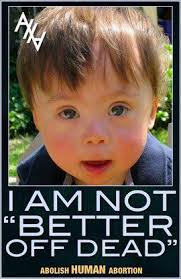

O.K., let’s try a different kind of case. I have known a few Down Syndrome victims, a condition whose detection often now leads to elective abortion; according to the 2014 edition of The Encyclopedia of Bioethics, 92% of pregnancies where the foetus is diagnosed with this condition are now terminated (“Abortion,” 1:14). I certainly consider the Down Syndrome victims I have known unfortunate. But not one of them wanted to die. Not one of them, once able to make the choice, would have chosen non-existence over the quality of the life he or she enjoyed. (Never mind the consequences of such a choice for an eternal soul—we are limiting ourselves here to considerations about the quality of the present life only, for the sake of argument.) Maybe some people in these situations would so choose; but it only takes one who would not to raise serious ethical questions about the quality-of-life case for abortion.

Down-Syndrome Child

What is that ethical dilemma? Well, here’s the next question: Would any of these people appreciate it if you unilaterally made the decision whether their lives were worth living for them without consulting them? Especially if you decided in the negative and proceeded to enact that decision! What would you be guilty of if you did so? Hmmmm.

Another question: What difference does it make if you make that preemptive decision about the value of someone else’s life before he or she can be consulted on the matter? Would this timing make that person’s murder (what else can we call it?) less heinous, or more? That’s a hard question. Here’s an easier one: Would you want to be deprived of the choice to determine for yourself whether your own life was worth living? If you would not want to be so deprived, how can you justify depriving someone else of the same . . . er . . . right to choose? That’s just the Golden Rule, right?

One might point out that once we have added the Golden Rule, we are no longer operating with a purely quality-of-life ethic. Something other than considerations of quality, the principle of “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” is now determining our choices. Exactly. A pure quality-of-life ethic would not really be an ethic at all. And therefore nobody has one. Little deontological bits of what Lewis called the Tao (like the Golden Rule) are always snuck in. The Golden Rule is, after all, pretty hard to argue against.

There are then many problems with a quality-of-life ethic, and I am not advocating one. But it is worth pointing out: Even when one is trying really hard to operate on a quality-of-life basis, once we add so simple and universally accepted a moral principle as The Golden Rule to our consideration of the facts, abortion is still very difficult to distinguish from murder and impossible to justify.

Donald T. Williams is R. A. Forrest Scholar and Professor of English at Toccoa Falls College. He is the author of nine books, including Stars Through the Clouds: The Collected Poetry of Donald T. Williams, Reflections from Plato’s Cave: Essays in Evangelical Philosophy, and Inklings of Reality: Essays toward a Christian Philosophy of Letters, 2nd edition, revised and expanded, all from Lantern Hollow Press. To order, go to http://lanternhollow.wordpress.com/store/.

A book that fights back against the darkness

Related